Moved to do something constructive with my anger and sadness about the SCOTUS debacle, I was reminded of work I’d done awhile back on The Furies of classical Greek myth and tragedy, and the ways in which the Western solution that we’ve cobbled together in response to the power of fury’s rage has been fragile at best, outright deadly at worst.

“That they could treat me so!

I, the mind of the past, to be driven under the ground, outcast like dirt!

The wind I breathe is fury and utter hate.” (Aeschylus, The Eumenides)

So spoke the ancient Furies, in Aeschylus’ Orestia, as the new gods of Olympus, led by Zeus, attempted to curtail their divine drive toward retribution for matricide. Today we can still hear them — or try to–in women’s voices when silenced and betrayed, in the fury of male aggression as power appears to be withdrawn, and on all sides of so many issues as tribal consciousness gathers steam in its own defense, and the image of ‘the evil other’ is cast back and forth. How we relate to the creative and destructive aspects of fury’s rage is reaching a boiling point, because life on our planet requires both openness to the winds of change that fury brings, and, empathy for the other, as the shift into global realization continues — one way or another.

Orestes and the Erinyes, Gustave Moreau, (c 1891)

Unceasing, relentless, implacable, and ever-grudging, the Furies avenge all betrayals and sins against deep relationships with a pitiless, ruthless intensity. We still find them at the interstices of all significant conflicts, those initiated by willful disregard of others humanity, those initiated by envy or greed, and even in those unintentional insufficiencies of love. As the ancient Greeks understood, the darker octaves of the “play” between relatedness and power usually draw blood. And it seems that this blood must be paid for in kind, by the dramas of guilt, retribution, and sacrifice, or, by a ritual transformation.The fury of wounding and betrayal can’t and shouldn’t be denied. It needs to be suffered through to its meaning and conclusion. Drinking the dregs of fury’s rage, our own and that of others, is part of the psyche’s move toward wholeness, into the heart of our own darkness, ‘leading us below’, as the Furies might say, where the dark fruit, a blood bond of communion with suffering, awaits.

How do we stay in a relationship to fury that is not just mutually destructive or patronizingly palliative? This is not easy. As William Barrett wrote in Irrational Man, “The easiest way to escape the Furies, we think, is to deny that they exist… The conspiracy to forget them, or to deny them, thus turns out to be only one more contrivance in that vast and organized effort by modern society to flee from the self.”

And in any case, as mythology and world events have repeatedly illustrated, if not given their due, the Furies will always have the last word in vengeance, even if it brings the whole house down.

Their story — and what it tells us about the fury and divisiveness that curse our land once again:

The Furies have been portrayed from Aeschylus to Albee as heavy hitters in the great web of human destiny. This may be because they symbolize a reality about destruction that belongs not only to emotional experience, but to the earthly existence itself — death and decay. Their mythic origins are placed very close to the beginning of time: either imagined as daughters of simply, “the Night”, or as the daughters of Uranos and Gaia, sky and earth. Hesiod recounted that as the primordial earth-father Cronos flung the severed phallus of his father Uranos toward the sea, the Furies were born from the blood that fell onto the earth, as the phallus received by the sea fathered Aphrodite, who would in turn mother Eros. The Furies speak of the dark, bitter side of the binding power of eros and attachment. And it is to betrayals of relationship and attachment that the Furies always return.

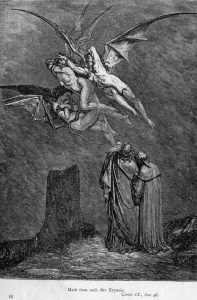

from Dante’s Inferno, by Gustave Dore, 1861

They came to be imagined as three winged, whip-wielding sisters, beastly predators when enraged, with serpent-filled hair and deadly claws, who lived in dreadful Tartarus or Dis, the region just before the Gates of Hades, reserved for those souls who committed terrible offenses. They appear in Dante’s Inferno, guarding and hovering over these Gates, fettering impure souls with unbreakable bonds, leaping on the guilty with avenging fury. The Furies emerge from their underground lair to punish the most heinous crimes, particularly murder, and especially matricide. Their names, Allecto, Tisiphone, and Megaira mean “unceasing”, “vengeance”, and “strange dark memory”. (Only Orpheus it seemed, was able to bring tears to their eyes, however temporarily.) They were also conceived as unpurified spirits of the dead, murdered ghosts, appearing as dark-colored doves, in tune with all the goddesses of fate and death who appear as black birds: crows, vultures, ravens; the Celtic Morrigan, the Egyptian Nekhbet, and the wrathful Valkyries.

The Murderer, by Franz von Stuck, 1861

The Furies frightful wailing was called a “binding hymn”, and like the Sirens song, it had the power to grip its victims, weaving a curse and casting a spell which reached all the way into the blood, chilling it, drying it up, and driving its victims mad. Like Nemesis and the Fates, the Furies through the maddening rage they invoke, bind us to what is most basic and elemental in our natures: the body, the emotions, and to a deep response towards integrity and maturity, however painful. The Furies binding, ‘primitive’ though it may be, is nevertheless, like all bonds and vows, an expression of a religious function. The patriarchal gods of Olympus, and later, western society and psychoanalysis, would try and break these bonds, both freeing and severing us from this single-minded devotion to the emotions and fury’s call, with unsettling and ambiguous consequences.

But the Furies place in psychological history derives primarily from the Orestia trilogy by Aeschylus, which concerns the resolution of the curse on the house of Atreus for the sin of hubris. (Philosopher Martha Nussbaum gives a full and provocative retelling of the story.) In brief: when Agamemnon returned home after the Trojan war he was murdered by his wife Clytemnestra, who, angered by his sacrifice of their daughter Iphigenia, had assumed rulership of Mycenae in his absence and taken a new husband. Apollo commands Orestes, son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra to avenge the murder of his father by killing his mother. Orestes protests, but afraid of Apollo’s curse and his father’s Furies, reluctant, but in the end compelled, he sides with his father and murders his mother, knowing full well that the Furies will drive him mad. And they do, immediately rising up to begin their pursuit and persecution of this most repulsive crime: matricide. Blood payment must be paid for matricide, deemed by the Furies infinitely worse than killing a king or husband.

“Your mother’s blood is on the ground.. The moist liquid is gone. But you in return must give to me to drain from you alive the red fluid from your limbs. From you would I take nurture…and having dried you up alive I will lead you below. Over our victim consecrate, this is our song – fraught with madness, fraught with frenzy, crazing the brain, the Furies’ hymn, spell to bind the soul, untuned to the lyre, withering the life of mortal man”. (Eumenides 341-6)

The Remorse of Orestes, by W.A. Bougvereau, 1862

Orestes tries in vain to escape. After a year of torture he attempts to take refuge at Delphi. Apollo orders him to Athens instead, to appeal to Athena to protect him. The play climaxes in the trial of Orestes on the hill of the Acropolis, before a tribunal of Athenian citizens, the first human jury. Apollo defends Orestes, citing the ultimate primacy of paternity, and the oracle of Zeus against ‘mother-right’. The Furies defend themselves.

“ When we were born such lots were assigned for our own keeping. So the immortals must hold hands off. Is there a man who does not fear this, does not shrink to hear how my place has been ordained, granted and given by destiny and god, absolute? Privilege primeval yet is mine, nor am I without place, though it be underneath the ground and in no sunlight and in gloom that I must stand”. (Eumenides, 389-96)

The vote by the Athenian citizenry is an uneasy tie, which is broken by Athena on the side of Orestes. He is freed from the Furies curse.

But at this acquittal, the Furies become completely enraged and threaten to destroy everything, the fertility of the earth, every infant in the womb.

“Gods of the younger generation, you have ridden down the laws of the elder time, torn them out of my hands. I, disinherited, suffering, heavy with anger shall let loose on the land the vindictive poison dripping deadly out of my heart upon the ground”. (Eumenides, 778-83)

But Athena intervenes, answering that although the Furies should not be “allowed to descend without limits into future generations” and must be tempered by reason, she also acknowledges the honor and wisdom in their claims, declaring that “These women have a work we cannot slight”, and agreeing that the moral fear they inspire is sometimes a good thing. She gives them a sanctuary near the Acropolis, and places the newborn children they threatened under their protection. The spirits of violent revenge are persuaded to accept a new dwelling in Athens, and reformed but honored, they become known as “the Eumenides”, the “kindly or gentle ones”, bless the land and its people, and are led off the stage in a dignified procession to their new abode. At the beginning of the play, the Furies were clothed as beasts, crouching dog-like creatures enthralled by the smell of blood. At the end, they stand erect, clothed in robes given to them by the citizens of Athens, and appear to the audience as human women. So began a trend towards their elimination: in later Greek tragedy their role becomes less and less deadly, until in Sophocles’ Electra there are no Furies at all to pursue Orestes and his sister. The curse of the house of Atreus was, seemingly, over.

But isn’t this cool barter suspicious — and why would the Furies take this strange deal at all? How quickly they seem to succumb to the teaser of respect and rationality. Has fury actually been ‘converted’, changing its essential nature and becoming well-disposed, or merely silenced and appeased? Is this a process of real transformation engendered by trust, or a “cover-up” which will not hold?

In a recent New York Times op Rebecca Traister wrote about the fate of women’s fury , “But then the world will come and tell you that you shouldn’t get mad again, because you were kind of nuts and you never cooked dinner and you yelled at the TV and weren’t so pretty and life will be easier when you get fun again. And it will be awfully tempting to put away the pictures of yourself in your pussy hat, to stuff your protest signs in the attic, and to slink back, away from the raw bite of fury, to ease back into whatever new reality is made… (and) you won’t yell anymore. What you’re angry about now — injustice — will still exist, even if you yourself are not experiencing it, or are tempted to stop thinking about how you experience it, and how you contribute to it. Others are still experiencing it, still mad; some of them are mad at you. Don’t forget them; don’t write off their anger. Stay mad for them, alongside them, let them lead you in anger.”

But the fragility of the ‘rational’ solution was recognized even by the classical Greeks. It was imagined as easily reversible. Euripedes, coming after Aeschylus, makes a dramatic point of inverting the process: in his plays noble women with kindly intentions become dog-like and thirsty for blood, and reason is exposed as a defense within the dynamics of revenge. The robes of humanity, Athena’s stock in trade, are easily removed. As even Judge Kavanaugh made quite clear.

Part II of this post explores that no matter what, when it comes to fury’s rage ‘what goes around always comes around” and that our collective psyche’s movement from a matriarchal to a patriarchal worldview has done very little to change this. Moreover, in an effort to control fury’s rage it has been stripped of it’s essential character and function, driven underground, only to break out in violent and dire crises such as we find ourselves in today.