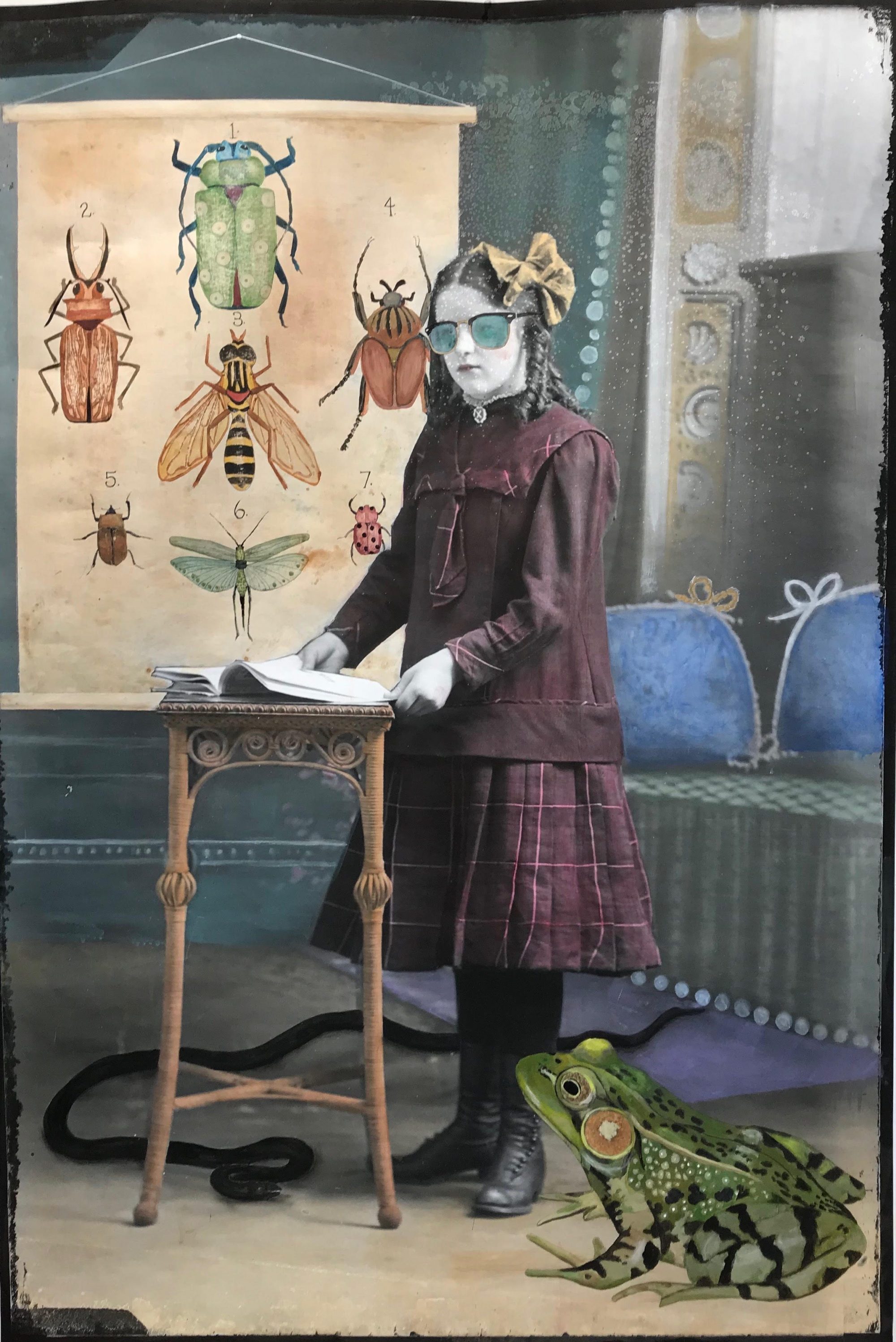

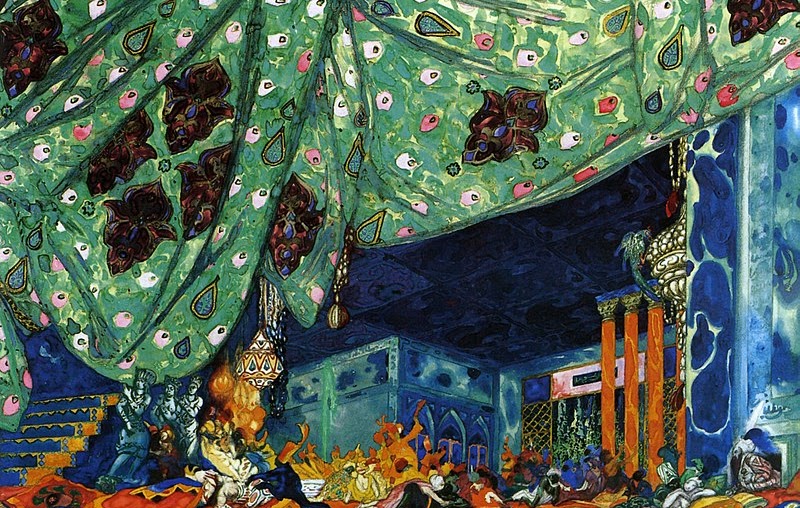

Set design for Scheherazade, (Ballet Russes), Leon Bakst

How do we stay sane and humane in what feels like an insane world?

Finding the deeper stories running underneath the runaway stories on the nightly news, well, for me it makes the difference between sanity and madness. It helps to parse the divine from the demonic, and most important, both of those from the human. I look for those stories by rooting around in the rubble of history, getting messy in the dustbin of mythology, and in the flights of imagination that lift off, like a flying carpet, from both.

There may or may not be a ‘deep state’ but there are deep stories. They allow us to share emotional essentials within ourselves and with each other. And there we touch down on common ground.

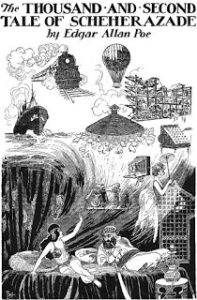

In One Thousand and One Arabian Nights (originating in a three volume Syrian manuscript from 14th-15thC.), the narrator Scheherazade tells stories that literally save her own life and the lives of others. It came to pass thus: the Sultan of Arabia, incensed when he discovers his Sultana and her handmaidens carrying on with his slaves, decides to take his revenge by marrying a virgin every night and then cutting off her head in the morning. The Sultan’s vizier was charged with finding the unfortunate girls, and soon candidates began to run out. The vizier’s daughter Scheherazade then volunteers — she has a plan. On the first fated night with the Sultan she tells him a bedtime story, making sure to leave off with a soap-opera worthy cliffhanger. Wanting to know how the tale ends, the Sultan postpones her execution.

And so it went on for one thousand and one nights, until the Sultan felt mercy in his heart and pardoned his Sultana.

As Marina Warner discusses in Stranger Magic, Scheherazade plays the part of an Arabian Penelope, delaying her fate by weaving an endless tapestry of stories. But unlike Penelope, she lets them grow larger and larger, holding the Sultan’s curiosity and finally, relieving his anger.

Equal parts imagination and enlightenment, fed by dreams, prophecies, memories, history, myth, and magic lanterns, Scheherazade’s stories expressed things essential to the human psyche. From tales told in bed in ancient Syria, fast-forward to the glow of a laptop in New York, Scheherazade has made her way over half a millennium: today, psychoanalysis, cognitive science, even the artifice of advertising have spoken the old truths in our modern tongues: great stories and the symbols through which they are often expressed move us in powerful ways that reason and rational thought alone do not — move us both creatively and destructively, individually and culturally. These ‘big’ stories and symbols provide a kind of intersubjective space through which we share the experiences of being human, bridging our own consciousness and the consciousness of others. They are public. We mammals transmit instantaneous non-verbal emotional signals to each other all the time; we human mammals are also transmitting those same signals, and our perception and thoughts via images and language, via symbol and story.

In our increasingly public world where the boundary between fact and fiction is being dissolved in the information stream, we are also continually subject to faux symbols and stories, to manufactured images and media spectacles. We recognize the authenticity of facts and fictions when they express the integrity of the present moment as it connects to the past and to the future. When they don’t, we think we can recognize the illusion. But is it so easy to tell the difference anymore, and do we really care?

We should. It matters a great deal whether we draw life from Scheherazade’s pharmacy of creative imaginati on or allow ourselves to accept a corporate or sociopathic doping with what’s been promoted for the enhancement of so-called ‘well-being , or just play dead with a ‘whatever’ ‘it’s all good’ propitiatory shrug.

on or allow ourselves to accept a corporate or sociopathic doping with what’s been promoted for the enhancement of so-called ‘well-being , or just play dead with a ‘whatever’ ‘it’s all good’ propitiatory shrug.

These days authenticity rests not in so-called transparency — which is easily manipulated — but in examining and exercising the imaginal projections and fantasies we weave around events. It means taking our psyches — not just our bodies — to the gymnasium of imagination. There we can parse the quick from the dead, the genuine article from the cultivated simulacrum. It’s hard work, but exercising our imagination’s projections onto events and onto others allows us to cultivate an ethical and empathic attitude toward one another and toward ourselves, an attitude informed not by normative behaviors or by political coercion, but by an understanding of the psychological patterns at play in our collective life, both the stories and symbols that have become rigid and hold us hostage, transfixed in horror or despair — and those that offer a way through.

Were Freud and Jung the heirs to Scheherazade’s talking cure? Indeed, in addition to a wealth of mythological figurines, Freud’s analytic couch was draped with an oriental rug from Turkey. Although Freud called it his “Smyrna rug,” it was actually made by the Ghashgha’i, a nomadic tribe for whom every carpet told a story. Nowadays, finding and sharing the deep narratives that underlie and propel collective currents is up to us as a social body, a kind of group “talking cure” that’s crucial as we try to become psychologically capable of something like democracy and cultivate an ethic of responsibility toward one another on a global scale.

Welcome to The Public Life of Symbols: Scheherazade 2.0